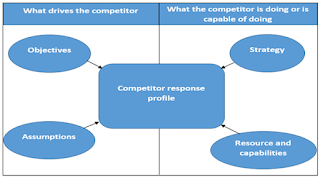

Components of competitor's analysis (Porter, 1980)

Michael Porter presented a framework for

analyzing competitors. This framework is based on the following four key

aspects of a competitor:

A competitor analysis should include the more

important existing competitors as well as potential competitors such as those

firms that might enter the industry, for example, by extending their present

strategy or by vertically integrating.

1.

Competitor's

Current Strategy

The two main sources of information about a

competitor's strategy is what the competitor says and what it does. What a

competitor is saying about its strategy is revealed in:

·

Annual shareholder

reports

·

Reports filed to Govt

Agencies

·

Interviews with

analysts , statements by managers , Press releases

However, this stated strategy often differs

from what the competitor actually is doing. What the competitor is doing is

evident in where its cash flow is directed, such as in the following tangible

actions:

·

Hiring activity R

& D projects

·

Capital investments

·

Promotional campaigns

strategic partnerships

·

Mergers and

acquisitions

2. Competitor's

Objectives

Knowledge of a competitor's objectives

facilitates a better prediction of the competitor's reaction to different

competitive moves. For example, a competitor that is focused on reaching

short-term financial goals might not be willing to spend much money responding

to a competitive attack. Rather, such a competitor might favor focusing on the

products that hold positions that better can be defended. On the other hand, a

company that has no short term profitability objectives might be willing to

participate in destructive price competition in which neither firm earns a

profit.

Competitor objectives may be financial or

other types. Some examples include growth rate, market share, and technology

leadership. Goals may be associated with each hierarchical level of strategy -

corporate, business unit, and functional level.

The competitor's organizational structure

provides clues as to which functions of the company are deemed to be the more

important. For example, those functions that report directly to the chief

executive officer are likely to be given priority over those that report to a

senior vice president.

Other aspects of the competitor that

serve as indicators of its objectives include risk tolerance, management

incentives, backgrounds of the executives, composition of the board of directors,

legal or contractual restrictions, and any additional corporate-level goals

that may influence the competing business unit.

Whether the competitor is meeting its

objectives provides an indication of how likely it is to change its strategy.

3 Competitor's Assumptions

The assumptions that a

competitor's managers hold about their firm and their industry help to define

the moves that they will consider. For example, if in the past the industry

introduced a new type of product that failed, the industry executives may

assume that there is no market for the product. Such assumptions are not always

accurate and if incorrect may present opportunities. For example, new entrants

may have the opportunity to introduce a product similar to a previously

unsuccessful one without retaliation because incumbant firms may not take their

threat seriously. Honda was able to enter the U.S. motorcycle market with a

small motorbike because U.S. manufacturers had assumed that there was no market

for small bikes based on their past experience. A competitor's assumptions may

be based on a number of factors, including any of the following:

· Beliefs about its competitive position past experience with a product

· Regional factors industry trends rules of thumb

A thorough competitor

analysis also would include assumptions that a competitor makes about its own

competitors, and whether that assessment is accurate.

Knowledge of the

competitor's assumptions, objectives, and current strategy is useful in

understanding how the competitor might want to respond to a competitive attack.

However, its resources and capabilities determine its ability to respond

effectively.

A competitor's

capabilities can be analyzed according to its strengths and weaknesses in

various functional areas, as is done in a SWOT analysis. The competitor's

strengths define its capabilities. The analysis can be taken further to

evaluate the competitor's ability to increase its capabilities in certain

areas. A financial analysis can be performed to reveal its sustainable growth

rate.

Finally, since the

competitive environment is dynamic, the competitor's ability to react swiftly

to change should be evaluated. Some firms have heavy momentum and may continue

for many years in the same direction before adapting. Others are able to

mobilize and adapt very quickly. Factors that slow a company down include low

cash reserves, large investments in fixed assets, and an organizational

structure that hinders quick action.

5. Competitor Response Profile

Information from an analysis of the

competitor's objectives, assumptions, strategy, and capabilities can be

compiled into a response profile of possible moves that might be made by the

competitor. This profile includes both potential offensive and defensive moves.

The specific moves and their expected strength can be estimated using

information gleaned from the analysis.

The result of the competitor analysis should

be an improved ability to predict the competitor's behavior and even to influence

that behavior to the firm's advantage.

Kotler

identified four common reaction profiles among competitors:

1. The laid-back competitor:

Some competitors do not react quickly or strongly to a

given competitor move. They may feel that their customers are loyal; they may

be harvesting the business; they may be slow in noticing the initiative; they

may lack the funds to react. The firm must try to assess the reasons for the

competitor’s laid- back behaviour (Example: LIC vs ICICI Prudential and other

private sector insurance companies in early 2000).

2. The selective competitor:

A competitor might react to certain types of assault and

not to others. It might, for example, respond to price cuts in order to signal

that these are futile. But it might not respond to advertising expenditure

increase, believing this to be less threatening. Knowing what a key competitor

reacts to gives a clue as to the most feasible types of attack (Example:

detergent wars involving Surf and Ariel in 2007).

3. The tiger competitor:

This company reacts swiftly and strongly to any assault

on its terrain. Thus HUL (Brooke Bond division) does not let any tea brand come

easily into the national market. The annual turnover of the tea industry is

Rs10, 000 crore and branded tea now occupies 60 per cent of the market. Tata

and HUL have major share in the national market and regional players like AVT, Harrison

Malayalam, WaghBakri, and Goodrick are limited to certain pockets only.

A tiger competitor that once it allows local STG brands

(like PDS in Kerala) to flourish in the market its brands (like Brooke Bond

Three Roses, HUL’s Lipton and Kannan Devan of Tata Tea will lose their shares

and the defender is going to fight to the finish till it gains edge over

others.

4. The stochastic competitor:

Some competitors (like Airtel, Vodafone, Reliance, and

BSNL in the mobile phone service provider category) do not exhibit a

predictable reaction pattern. Such a competitor might or might not retaliate on

any particular occasion, and there is no way to forecast what it will do based

on its economic history, or anything else.

Henderson’s

comments on this have been summarized by Kotler in the following ways:

a. If competitors are nearly identical and

make their living in the same way, then their competitive equilibrium is

unstable (for example, very little or no service differentiation among GSM

service providers).

b. If a single major factor is critical then

competitive equilibrium is unstable (here the factor is talk time).

c. If multiple factors may be critical

factors, then it is possible for each competitor to have some advantage and be

differentially attractive to some customers. The more the multiple factors that

may provide an advantage, the more the number of competitors who can coexist.

Each competition has its competitive segment

defined by the preference for the factor trade-offs that it offers (here the

usage of WAP, MMS, GPRS are limited, hence very low percentage utilization of

value added services).

d. The fewer the number of competitive

variables that are critical, the fewer the number of competitors (here the

market is regulated by TRAI).

e. A ratio of 2:1 in market share between any

two competitors seems to be the equilibrium point at which it is neither

practical nor advantageous for either competitor to increase or decrease share

(still profitability and steady growth is yet to been witnessed in the market).

No comments:

Post a Comment